Rachel Balick

Editor’s note: This is the first part of Pharmacy Today’s ongoing coverage of structural racism.

The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago,” a Chinese proverb says. “The second-best time is now.”

Social determinants of health are not a new concept in pharmacy. We all see that there are significant disparities in health care access and outcomes. We know we have a long way to go before we can earn the trust of people who’ve been abused and disrespected by the health care system.

In 2020, the abstract became the literal, and people died. They suffered and died because the government, health systems and providers, and society at large had failed to address inequity before disaster struck. As COVID-19 disproportionately killed Black individuals, protesters around the country cried for racial justice and an end to hate, racism, unequal treatment, and all forms of discrimination.

Now it is plain: No one can ignore the connection between historic oppression and poorer health outcomes, a reality that is far from limited to COVID-19. There is no neutral: Those who do not proactively work to dismantle structural racism condone structural

racism. And so, pharmacy dug into the hard work of examining its role in the problem—and in the solution.

Unequivocal

“Black lives matter,” APhA Executive Vice President and CEO Scott J. Knoer, PharmD, MS, FASHP, wrote in a January 2021 Chain Drug Review column. “That’s a fact, not a political statement. Black lives matter.”

Structural racism is real and it’s pharmacy’s problem, he wrote. “APhA owns our role in this.”

In June 2020, APhA signed on to a joint letter, National Pharmacy Organizations Unite to Take a Stand Against Racial Injustice, initiated by the National Pharmaceutical Association (NPhA). Established in 1947, NPhA is dedicated to representing the views and ideas of minority pharmacists on issues that affect health care and pharmacy, promoting racial and health equity, and advancing the standards of pharmaceutical care among all practitioners. About a dozen national pharmacy organizations also signed the letter.

“Adding to the challenges of the global pandemic of COVID-19, which disproportionately impact communities of color, there is a greater public health crisis plaguing our country: racism and discrimination,” the letter read. “People of color and other marginalized groups experience a continuum of systemic racism, discrimination, and injustices that result in ongoing health inequities created by numerous factors impacting social determinants of health.”

That same month, the APhA Board of Trustees created an action plan to influence personal, professional, and societal change, including the formation of the APhA Task Force on Structural Racism in Pharmacy. The task force would focus on the ways APhA and the profession pursue policy, communications, and activities geared at dismantling racial injustice.

Agents of change

Chaired by CDR Andrew Gentles, PharmD, BCPS-AQ ID, the task force comprises a diverse group of APhA members. “We have been really deliberate in terms of making [our events, such as town halls] accessible to even nonmembers, because we think this issue extends beyond that,” he said. “This is for the entire pharmacy profession.”

Sandra Leal, PharmD, MPH, FAPhA, CDE, took on the mantle of APhA President during the APhA2021 Virtual Annual Meeting & Exposition—the same meeting where the Task Force on Structural Racism in Pharmacy held its most high-profile town hall so far.

“The fact that we’re having the conversation and having that awareness is phenomenal to me—that it’s something that we’re now putting into our programming, and actually having discussions about,” Leal said.

Leal cheered CDC’s recognition that racism is a public health crisis, an action that she views as a real opportunity for pharmacy to become agents of change. “How can we lean into that and actually do something to address that? How do we use the power of our accessibility to create better conditions for patients?” she said. “We need to be an advocate for these individuals and ask the hard questions.”

“I do not believe that [pharmacists] have been agents for change,” said Michael A. Moné, BPharm, JD, FAPhA, a member of the APhA Task Force on Structural Racism in Pharmacy. “We have been on the sidelines watching things happen without actively engaging ourselves in understanding and participating in the movement for change.”

Find the lens

“We certainly do need allies in this space,” said Gentles, who believes the work should aim to create more allies by ensuring future pharmacists understand structural racism, inequity, and implicit bias in pharmacy before they start their career.

“If we want to help from the pharmacy institutional perspective, let’s look at the pipeline. We want to make sure that pharmacists graduate with the right lens to racial equity and racial justice, so they have a knowledge of what these issues are before they enter into practice,” he said. “The pharmacy education system should be inclusive of the history of racism and its impact not only in terms of the pharmacy profession, but also how it impacts our patients and their lives.”

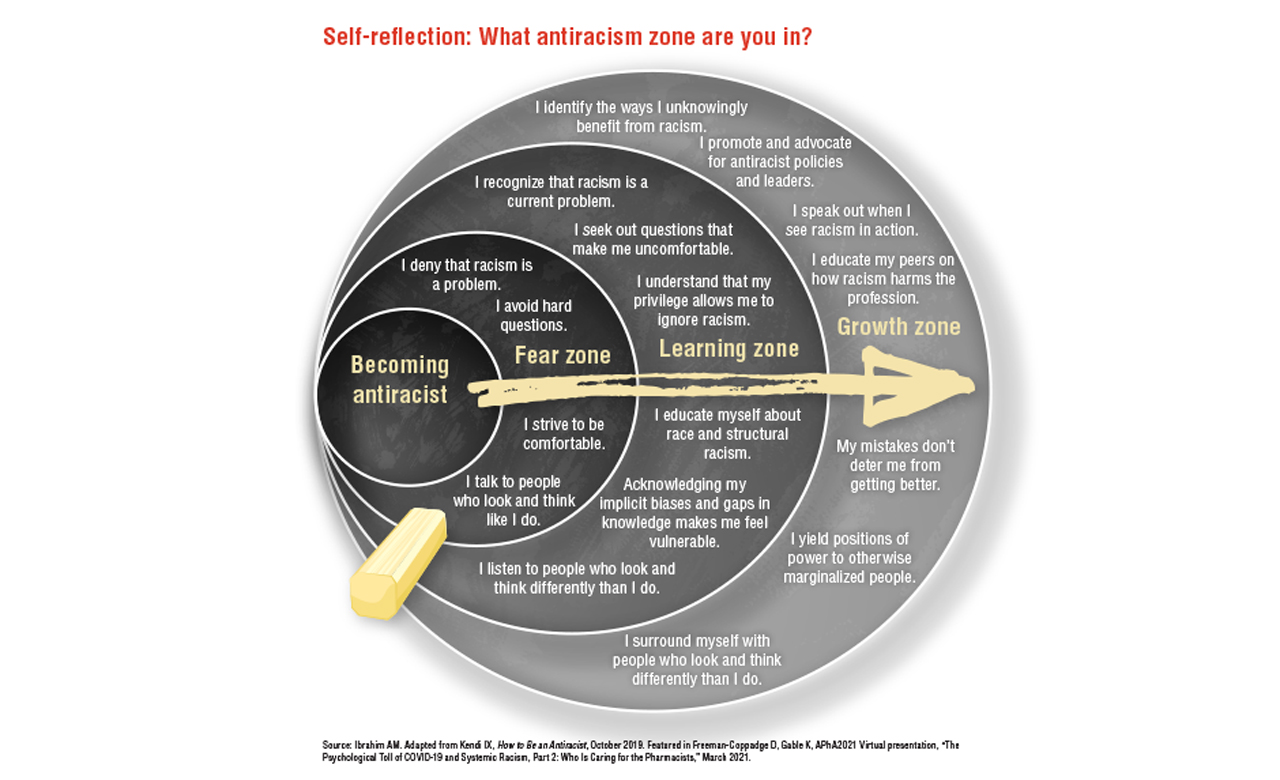

Indeed, pharmacy education is an opportune time to engage in self-reflection and to participate in difficult conversations about structural racism.

Vibhuti Arya, PharmD, MPH, is an expert in racial dialogue and one of pharmacy’s most prominent voices on structural racism and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Arya said her work centers on transformative change. “My focus is on systems of oppression—the intersectionality of lots of different power dynamics—and it’s about accountability,” Arya said.

“DEI educators talk about how work on equity shouldn’t be just icing on the cake. It should be baked into the cake,” Arya said.

What does that mean when the cake is real life? Often it means creating a strategic plan that considers DEI’s place in organizational priorities. “DEI has to be key to [an organization’s work], not just a checklist. The topic touches everything.”

Say you’re having a conversation about diabetes. “When we teach our students to talk to our patients, we’re teaching them to be kind and compassionate. We’re also actively having a conversation about how, implicitly, you might be incorrectly assuming about all the obstacles that your patients face,” Arya said.

Any assumption should be identified, challenged, and verified. It sounds simple, but “a lot of us, in times of crises, in times of heightened anxiety or pressure, operate from our automatic subconscious minds.” If we are not aware of the patterns that we exhibit, we may unconsciously perpetuate racism.

“Then, even beyond the interpersonal, beyond any one particular incident, we have to critically examine the systems of subjugation that our policies and norms perpetuate,” said Arya.

Diversity and antiracism aren’t the same

“A common thing people tell me is that their workforce, team, leadership, students, faculty, whatever it is—has become so much more diverse. ‘Our students are diverse. Our dean is a woman. We’ve made great strides,’” Arya said. “Great. But the policies, procedures, systems, the processes haven’t changed to reflect that. That’s the ‘baking into the cake.’”

She recommends that people and institutions be thoughtful about how they approach inequity and structural racism, making deliberate, intentional space for tough conversations. Every level of an organization should be attuned to and present for those conversations—especially leadership.

“Conversations on implicit biases and how we view the world may seem very abstract, but they’re necessary,” Arya said. “If the folks you’re hiring do not understand how this conversation impacts them, that’s going to be a problem. It’s about extending our compassion to center the marginalized voices.”

Arya described a program that touted its decision to prioritize Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) candidates for admission. “What they communicate is one thing, but the underlying narratives and environment are even more telling,” she said. “I’m always interested in what that means to them, how it manifests across their decisions. People often use the same language, but that language and those words can mean very different things to different people.”

She can appreciate the effort to bring in more diverse students, but that’s just scratching the surface. “How are you viewing them in your program? If a person of color is underperforming, how do you deal with that? And often I hear comments about lowering standards for quality,” Arya said. “Underrepresented doesn’t mean underprepared, but people see this as doing BIPOC [students] a favor.”

Arya believes that kind of narrative should be brought to the forefront, discussed, and reframed. “What you want to shift to is, ‘Hey, we’re severely lacking perspectives that differ [from our own]. That perspective is valuable to us. That person is an asset to us,” she said. “You see how that power shifts? It’s ‘They’re so lucky to be here’ versus ‘We are so lucky to have them and need their perspective.’”

The representation piece is important: People who look like the community they serve can relate to it more or understand it better. “But the people who are making decisions about promotion and tenure, performance evaluations, et cetera, also need to have conversations about implicit bias. What does professionalism mean to them? The use of ‘professionalism’ could basically be a stand-in for ‘assimilation.’ ”

Many things about what professionalism should supposedly look like are unintentionally problematic for BIPOC students—like being told what clothes and hairstyles are professional. “There are such different standards for folks of color, and they have to sort of defend being anything other than what you see through the normative lens,” she said. White ideologies about professionalism alienate students of color and BIPOC members of teams and leadership. “We’re not allowed to bring all parts of ourselves to the table. We have to leave parts of ourselves out.”

Inclusion is not equity

A new face on an unchanged skeleton can even be damaging. “I think it is unethical to bring people into an organization without creating the environment for them to actually thrive. Not just survive, but thrive,” Arya said.

That’s a major part of what Melissa Durham, PharmD, MACM, APh, does as University of Southern California (USC) School of Pharmacy’s assistant dean of DEI.

Durham is a white woman. “Because I come from such a position of privilege due to the color of my skin, taking up space in conversations about systemic racism isn’t usually the best strategy,” Durham said. “Often my work as an ally and advocate is to quietly maneuver in the background to make systemic change.”

It’s also her job to ensure BIPOC students and colleagues have meaningful support. “But of course, I’m not always quiet. I see it as my role to help lift up the voices of others who are minoritized, historically underrepresented, or oppressed,” Durham said, “and to call out racist or discriminatory ideas, policies, practices, and subtle acts of exclusion when I see them.”

One problem area is a lack of diversity among academic faculty. “Academia is historically a very white male–dominated type of institution,” Durham said.

“We really need faculty to look like and have shared experiences and backgrounds with the students they’re teaching in order to provide the type of education that will prepare our students for future practice. It is about excellence in education above all.”

She seeks to remedy the issue behind the scenes by building a pipeline of future educators.

“We need to work with diverse groups of students who may be interested in becoming faculty,” Durham said. “We need to teach them about academia, mentor them, and prepare them for their career paths ahead.”

That is, in a nutshell, how Durham sees herself in the DEI landscape.

“If you are a white person and are unsure of what role you can play, just have the courage to keep showing up, keep supporting, and keep amplifying the voices of those who do not share your privilege,” she said.

Facing your flaws

“We all have racist ideas because we are all socialized in a society founded in white superiority. Once you start to do the work to look inward, you will start to see it within yourself and everywhere else,” Durham said.

“As a privileged white person, you have the option to go about your life and not ever have to think about racism. And even if you consider yourself aware, or woke, or progressive, you may figure that other people are taking care of it and that it is not your job, or you don’t know enough to do anything about it.”

That was more or less Durham’s attitude for a long time. What she saw over the last several years changed all that. “It became clear that it was no longer an option to not say anything, not take action, or to assume that others are going to do it,” she said. “I was fed up and felt like I had to do something.”

Durham believes antiracism work, although not new, has ramped up due to heightened awareness of racial issues—police violence, COVID-19’s disproportionate impact, the spike in hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islander community—and the lives on the line. It’s a life-or-death situation.

A lot of white people ask themselves uncomfortable questions: “How could I have not known? Why didn’t I see what racism was like in our country? I’m still a good person, right?”

“Racism is tied so much to, ‘You’re a good person. You’re a bad person.’ We need to get rid of that narrative, because racism just is,” Durham said.

Sometimes Durham questions if, as a white woman, she should be working in the DEI space.

“But there are times where I can really make a difference, because the burden has been carried by people of color for way too long,” she said. “BIPOC folks are exhausted. It’s retraumatizing. It’s heavy. It affects their mental health. The collective of our entire profession really needs to get on board and help with this.”

The eager but anxious

“White people are not conditioned to confront racial stress. It’s like a muscle you have to exercise. It’s uncomfortable and it takes practice, because we aren’t conditioned to see ourselves in racial terms,” Durham said.

She has seen examples of this as a member of the structural racism task force.

“We’ve had some town halls where there’re a lot of [APhA members] who are white. They want to do something, but they don’t know where to begin,” she said. “It’s helpful if I take those people on.”

So, what does Durham tell them? The process for an individual person,

she said, is not that different than it is for an organization—academic, for example, or APhA itself. “You have to do the work to look within, and also see where you can start to make changes to the systems around you.”

Durham usually recommends books to read, Instagram accounts to follow, trainings to take. “I [advise starting] with books,” she said, but regardless, the point is that self-work comes first.

Explore your own background and how that shapes your perspective: How were you raised? What messages did you receive from people who influenced you growing up, like your family and teachers? What systems and structures shaped you?

“Then you critically evaluate which ideas are like yours and which ones have been given to you along the way,” she said.

Then you start to look outward: What in my immediate world—something unfair or inequitable—can I make better? What disproportionately affects people of color, the LGBTQ community, individuals with disabilities? Where do I have privilege? What are some little changes I can make within my area of influence? “Something really small can have a big impact,” Durham said.

After a recent talk about health justice, Durham caught up with an alumnus of her program. The woman told her that after listening to Durham’s talk, she realized she could make one change to the wording of a policy in her APPE syllabus to make it more equitable.

“It can be, ‘How can we create a space that is equitable for people who have children and help them thrive at work or in school?’ Or you can do something even more simple, like removing gender binary language or veiled racist language about ‘professionalism’ from a school dress code.”

As you develop and find ways to make change, you branch out further: How can I show up to bigger spaces, maybe within my profession or my organization?

Always, always be learning along the way. “It’s a lifelong process. It’s not like it’s one and done. You don’t read one book or attend one training and say, ‘I got this, I’m all about antiracism and equity now.’ You continue to look for diverse perspectives and de-whitewash your world,” Durham said.

Pushback

There are plenty of people who take structural racism work as a personal affront or an indictment of the characters of individuals, organizations, governments, and even American ideals—an attempt to destroy the very fabric of the nation, punish people for their beliefs, tear up the flag, “cancel” people for exercising free speech. They might say that the work drives a left-leaning political agenda, and that the word “racism” is used to be intentionally divisive.

“It is a tough word to deal with, especially for those who have never experienced racism firsthand and have never examined their own beliefs,” said Michael A. Moné. That’s what’s good about it.

“I would like my colleagues to have a visceral reaction, not just an intellectual reaction. I want them to become activated,” Moné said. “I want them to think about the profession and think about their place in it—their place in society at large. And most of all, I want them to become mobilized to fight against racism in all its manifestations.”

The bigger picture

Either way, it’s a mistake to get preoccupied with the word “racism.”

“I think people really should focus on the word ‘structural,’ the broad general policies that have been laid in society for decades and that result in inequities,” such as redlining, Moné said.

Redlining was a system in which banks and real estate institutions drew literal red lines around predominantly BIPOC neighborhoods on maps. They then refused to provide borrowers with home loans, deeming the loans “too risky.”

White families a few blocks away got the loans to become homeowners. Their home equity financed their kids’ college educations. They amassed wealth to pass down from generation after generation, ensuring each had a nest egg in perpetuity.

Denied the opportunities to get mortgages, Black families couldn’t grow their wealth through equity in their homes. These areas had and have a lower tax base, which leads to poorer infrastructure and affects school quality. Fewer families could send their kids to college and get access to higher-paying jobs.

All those things are still true. Officially, redlining was outlawed in 1968, but the passage of a law cannot reverse damage inflicted long ago.

“Racial equity [will] exist when members of the pharmacy profession who are most impacted by the structural racism that manifests itself in existing policies and procedures are themselves involved in the development of new policies and procedures that do not have as their foundation or effect a disparate racial impact,” Moné said.

“We’re here to have a conversation, not a debate,” Arya said. “People are dying, literally.”

Structural racism glossary

» Diversity: The various backgrounds and races that comprise a community, nation, or other group. The term not only refers to heterogenous characteristics and identities (e.g., race, gender, religion, sexual orientation) but recognition, respect, and understanding of these differences.

» Ethnicity: The social characteristics that people may have in common, such as language, religion, regional background, culture, foods, and traditions.

» Equity: Whereas equality refers to dividing resources in identical amounts, equity describes dividing resources proportionally as needed to achieve fair outcomes for all. Paula Dressel of the Race Matters Institute wrote in a blog that “the route to achieving equity will not be accomplished through treating everyone equally. It will be achieved by treating everyone equitably, or justly according to their circumstances.”

» Implicit bias: In a 2009 primer for the National Center for State Courts, UCLA law professor Jerry Kang described implicit bias as the “thoughts about people you didn’t know you had,” including unconscious and unchallenged assumptions, stereotypes, beliefs, and attitudes. All individuals have some degree of implicit bias without being aware of it.

» Institutional racism: The Aspen Institute defines institutional racism as “the policies and practices within and across institutions that, intentionally or not, produce outcomes that chronically favor [a racial group] and [put another] racial group at a disadvantage.” Institutional racism can manifest as school disciplinary practices that punish students of color more often and more severely—even expel them—than white students for the same infractions; this also occurs within the justice system, in employment, and in health care settings.

» Intersectionality: This term was coined in 1989 by American lawyer, civil rights advocate, philosopher, professor, and critical race theory scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe how race, class, gender, and other individual characteristics “intersect,” overlap, reinforce each other, and compound oppression and discrimination.

For example, an antidiscrimination law may address race or gender, but it does not address both; that makes it difficult or impossible for a member of more than one minoritized group to get justice.

» Microaggressions: Columbia University’s Derald Wing Sue described microaggressions as the “everyday slights, indignities, put downs, and insults that people of color, women, LGBT populations, or [others] who are marginalized [experience] in their day-to-day interactions.” Intentional or unintentional racial microaggressions are brief but common—even daily; can be verbal, behavioral, or environmental; and are hostile, derogatory, or negative. Perpetrators of microaggressions may not realize that they use them.

» Race: Unlike ethnicity, “race” describes categories assigned to demographic groups based mostly on observable physical characteristics, such as skin color, hair texture, and eye shape.

» Racial equity: According to the Aspen Institute, “a reality in which a person is no more or less likely to experience society’s benefits or burdens just because of the color of their skin. … In a racially equitable society, the distribution of society’s benefits and burdens would not be skewed by race.” Racial equity requires not just equal opportunity but equal outcomes.

» Social determinants of health: Conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.

» Structural racism: There is no official definition, but there is consensus about its manifestations and causes. In a February 2021 New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) article, Bailey and colleagues said that “[structural] racism is not simply the result of private prejudices held by individuals, but is also produced and reproduced by laws, rules, and practices [that are] sanctioned and even implemented by various levels of government, [embedded] in the economic system as well as in cultural and societal norms.”

Structural racism is not something that individuals or institutions intentionally practice; it is a historical and cultural system that throughout history has buttressed white supremacy, perpetuated inequity, and “allowed privileges associated with ‘whiteness’ and disadvantages associated with ‘color’ to endure and adapt over time,” according to the Aspen Institute. “[Structural] racism [work] takes direct account of the striking disparities in well-being and opportunity [that] come along with being a member of a particular group and works to identify ways in which these disparities can be eliminated.”

» White fragility: Coined in 2011 by author, scholar, and antibias consultant Robin DiAngelo—who in 2018 published the bestseller White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism—the term refers to “a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves.” White fragility can manifest outwardly as anger, crying, fear, denial, guilt, shame, dismissiveness, defensiveness, and resentment.

Some white people may perceive the suggestion that something is racist as a personal attack instead of an opportunity to learn or reflect—this is an illustration of “white fragility.” These responses can direct focus to their hurt feelings and away from a Black person’s experiences. “The simplistic idea that racism is limited to individual intentional acts committed by unkind people is at the root of virtually all white defensiveness on this topic,” DiAngelo wrote in her book.

» White privilege: Refers to white people and communities with historical and contemporary advantages, such as access to quality education, decent jobs, livable wages, homeownership, retirement benefits, and wealth. These advantages accumulate across generations. Peggy Macintosh of Wellesley Centers for Women describes white privilege as “an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in every day, but about which I was meant to remain oblivious.”

Sources: Aspen Institute, “11 Terms You Should Know to Understand Structural Racism,” July 2016; Bailey ZD, How Structural Racism Works—Racist Policies as a Root Cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities, NEJM, February 2021; Coasten J, “The Intersectionality Wars,” Vox.com, May 2019; DiAngelo R, White Fragility, International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 2011; DiAngelo R, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, 2018; Dressel P, “Racial Equality or Racial Equity? The Difference It Makes,” Race Matters Institute blog, April 2014; Howard L, “What Is White Fragility,” verywellmind.com, April 2021; HHS, Healthy People 2030; Kang J, Implicit Bias: A Primer for Courts, August 2009; Kendi IX, How to Be an Antiracist, 2019; McIntosh P, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack, Peace and Freedom,” July/August 1989; Merriam-Webster Dictionary; Sew DW, Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice, American Psychologist, 2007.

Asking, listening, processing

Moné is a white man who has worked on DEI issues long enough to learn a lot about being an ally and an antiracist. He knows how difficult conversations about racism can be, even for their most well-meaning participants—especially for their most well-meaning participants, at times. And he has some recommendations for people who have never experienced racism and are taking their first steps into unfamiliar terrain.

One thing right off the bat: “People may ask questions not to seek to understand, but rather to demonstrate how much they already know or think they know,” Moné said. Long story short: Don’t do that.

Explore your intentions before you ask questions. “The first, most important point is to be open and honest. Do your research. Read about racism. Only then can you ask a purposeful question,” he said.

The research can be useful for those who bristle at the word “racism” or don’t understand why it’s used. It helps to learn more about what it means and how it functions in society. “Get a grasp of the foundation,” Moné said.

Trust

Know the person you’re asking, he said. “You have to have the kind of relationship [where] you feel comfortable [with each other]. Ask them, ‘How does [racism] affect you, or how has [it] affected you? Does it continue to affect you?’”

That relationship doesn’t mean the conversation will be easy, Moné said. “The point to be made is that it’s not a comfortable conversation, especially if you have a relationship with somebody who can turn around and say, ‘Do you remember when you said this?’”

Most people will say they don’t. “Well, the person you’re talking to remembers it, and they will tell you how it made them feel. That [reflects on] you as an individual and on you as an ally.” But, Moné said, “I think for most folks, their [missteps] are unintentional. They just didn’t think about the impact on the other person.”

There begins a deeper discomfort. “You have to [recognize] that you may hear things about yourself, sometimes in the abstract and sometimes in real time, that you [don’t] like.”

Productive mindsets

Stay present. “Breathe and breathe again. Don’t get defensive. Don’t start thinking about your answer. Just listen,” Moné said.

Getting defensive or feeling personally attacked is natural, but not necessarily appropriate in this context. “If you asked for the conversation, it’s not about attacking you personally—it’s about growth,” he said. “Most folks are OK with growth as long as it’s on their terms. That’s the problem. This may not happen on your own terms.”

Resist counterproductive urges. “Don’t bring up false equivalencies—that seems to be a manner by which folks today try to deflect. ‘Well, what about so and so? What about this? What about that? That’s not right, either,’” he said. “It’s not about the what-abouts. It’s a conversation about the things that you either did or didn’t do when you should have.”

Don’t push the discomfort away. “If somebody’s going to tell you something [like that about yourself], you really need to seriously think about what you heard. Then begin to make positive change, learning more, reading more, being a better person.”

Bring it full circle. “Ultimately, you must assess if you are a better person by having a subsequent conversation with the person you selected,” Moné said. “Ask how and whether you improved.”

Implicit bias affects patient care

Alex C. Varkey, PharmD, MS, FAPhA, is a member of APhA’s Board of Trustees (BOT) and director of pharmacy services at Houston Methodist Hospital. His position gives him perspective on how implicit bias hurts patients. “Implicit bias truly exists, and it still affects patient care today,” he said.

Varkey recently read online about a physician’s account of treating an unresponsive African American man at another institution. Hospital staff members immediately identified him as a drug-seeking patient who had overdosed. “That’s the label they gave this individual when they rolled him into the hospital.”

The physician reached into the man’s pocket and found his medical identification, which noted a history of seizures. “All of a sudden the conversation changes to, ‘Did anyone do a toxicology report? Does anyone know for sure that this person is a drug seeker? Has anyone looked at his arms for any signs of I.V. drug abuse?’ ”

None of those things had been done. The staff had already assumed that he was “someone who was doing something illegal or nefarious to get into the situation,” without doing the proper vetting, Varkey said. In the absence of information, he said, people create stories simply on the basis of how someone looks. “But the stories aren’t true.”

A pharmacist can practice bias in many ways without even knowing it, Varkey said.

Picture a pharmacist who sees someone who’s never been in the pharmacy before—and that person is asking for a package of insulin syringes. “Just based on how they look, you might wonder, ‘Well, why do you need syringes?’ ” The pharmacist might then look up the person in the computer; if they find no prescriptions for insulin, that can lead to questions about who the syringes are for. “Maybe they say they’re picking them up for their grandmother. And then you might ask, ‘What’s your grandmother’s name?’ It becomes an interrogation.”

Patients with prescriptions for controlled substances—especially those who are BIPOC—often face the same interrogation or are turned away at the pharmacy counter. “Are you [more closely] scrutinizing a particular prescription because of how someone looks or appears, as opposed to the validity of the diagnosis and the doctor’s office where this prescription is coming from?”

Implicit bias can emerge from company or store policies. “If the leaders of that store warn, ‘We’re in a location where [prescription drug abuse] is rampant, and we will not contribute to the problem,’ while that may be a valid concern, it could lead to that thought playing in the back of your mind,” Varkey said. “You might think, ‘I need to look out for drug-seeking behaviors,’ but then unintentionally shut out the patients who legitimately need care simply because you’ve already cast a broad, biased judgment.”

Every health care provider, health care institution, every pharmacy education program—everyone—owes it to their patients to take a critical look at where they can get better, he said.

The price of passion in a troubled world

There is scarcely a pharmacy news story on social determinants of health and vaccine hesitancy that doesn’t include Lakesha M. Butler, PharmD, BCPS.

Butler is a former NPhA president and the first director of DEI at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy, where she is also a clinical professor of pharmacy practice. She’s a highly visible and respected voice on health inequities.

She’s also a human being.

Passion, purpose, and trauma

Her success comes at a personal cost. “I absolutely am passionate about this topic, mainly because of my own personal experiences,” Butler said.

“That passion intertwines with purpose, and because I’m so passionate and operating from a stance of purpose, it often doesn’t feel like work.”

But it is precisely those personal experiences that can affect her capacity to keep moving.

“Reliving some of those experiences is retraumatizing not only when I do this work, but continuously. We are still experiencing [racial injustice],” Butler said.

“That is the epitome of what we call ‘racial battle fatigue.’”

Over the last year, she’s endured intense racial battle fatigue and race-based trauma—which can result, for example, from seeing individuals who look like you being killed day after day. The trauma of racism takes no breaks, never slows down, never offers the respite to fully heal.

“It’s very easy to get to a place of being numb because it happens so frequently,” Butler said. “The adrenaline is constantly flowing because of the fight, flight, or freeze response to trauma.”

Butler is in good health, but she worries about her patients.

“I feel that in the Black community and in communities of people of color, we have wounds—what I call battle wounds—that have continued not to heal and are becoming a normal part of our body. However, we don’t completely know how that is affecting us internally. It’s very disheartening to think about the effects of all of this.”

Building coalitions

“When I really got into this full force in response to what’s been going on in our country, I didn’t necessarily have in mind the importance of self-care and of being self-aware about how this work was affecting me. And oftentimes, I was extremely exhausted,” Butler said.

Butler has reached a place where she knows when to say no and is very intentional about her participation in these spaces, but it’s not effortless: Self-care is crucial, but pressing pause can be a struggle.

“I often feel that, if I or other colleagues who are passionate about this work are not the ones sharing experiences and educating others, the education won’t necessarily get done,” said Butler.

To ensure passion is compatible with personal well-being, its burdens must be shared. Butler hopes that the work that she and her colleagues have done will foster a coalition of individuals passionate about racial and health equity—one that includes members who identify as people of color and members who don’t.

“We really want to create this coalition so that when I need that time to take a step back, there are others who are willing and capable to step up to the plate.”

The fight goes on

The work is hard on the body and mind, but the rewards can be sweet.

“When I’m in spaces where I’m educating others and I see the growth in those individuals, those are bright days for me. Those days really make this work worthwhile,” Butler said.

She often thinks of her ancestors who were slaves and those who were in the civil rights movement, and their fight for equal rights and opportunities. “I feel as if I owe it to them. Because of their fight, the country did move in a positive direction,” she said. “I was able to go to a predominantly white institution, and I’m able to live now in a predominantly white neighborhood because of the effort they put into changing policy dismantling some of the quite oppressive systems.”

That fight lives within her, too.

“I truly want to be a part of the solution. I want to make this world a better place for my kids. I don’t want them to have to go through the same marginalization that I have gone through,” Butler said.

“It’s an honor to be able to do this work, while challenging, but it’s also a responsibility for me. I’m very grateful to be a part of this movement and to help to continue to move us forward.”

APhA Task Force on Structural Racism in Pharmacy

CDR Andrew Gentles, PharmD,

BCPS-AQ ID, chair

APhA Trustee and senior regulatory program coordinator

FDA

Washington, DC

Melissa J. Durham, PharmD, MACM, APh, vice chair

Associate professor, clinical pharmacy; and assistant dean of diversity, equity, and inclusion

University of Southern California,

Los Angeles

Vibhuti Arya Amirfar, PharmD, MPH

Professor, St. John’s University

Clinical advisor, policy, resilience, and response

NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, New York

Leonard Edloe, ThM, PharmD

Retired pharmacist and CEO,

Edloe’s Professional Pharmacies

Pastor, New Hope Fellowship Mechanicsville, VA

Meryam Gharbi, PharmD

Pharmacist

Walgreens Pharmacy

Salisbury, MD

Michael D. Hogue, PharmD, FAPhA, FNAP, ex officio member through April 2021

APhA Immediate Past President

Loma Linda, CA

Scott Knoer, MS, PharmD, FASHP, ex officio member

Executive vice president and CEO, APhA Washington, DC

Sandra Leal, PharmD, MPH, CDCES,

ex officio member

APhA President, Tucson

Anne Lin, PharmD, FNAP

Dean and professor, Notre Dame of Maryland University School of Pharmacy

Baltimore

Michael A. Moné, BPharm, JD, FAPhA

Principal, Michael A. Moné and Associates, LLC

Powell, OH

Juan Rodriguez, 2022 PharmD candidate APhA–ASP National President

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Pharmacy Memphis

Parth Shah, PharmD, PhD

Assistant professor, Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research, Fred Hutch

Seattle

Adrienne Simmons, PharmD, MS, BCPS, AAHIVP

Director of programs, National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable at the Hepatitis Education Project

Washington, DC

Theresa P. Tolle, BPharm, FAPhA

APhA President-elect

Sebastian, FL

Brian Lawson, PharmD, APhA staff liaison

Associate executive director

Board of Pharmacy Specialties Washington, DC