Sonya Collins

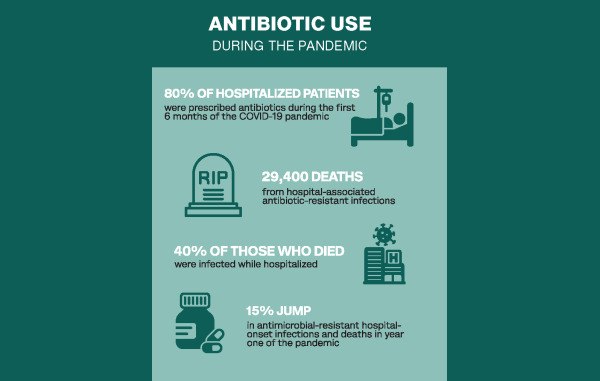

Eighty percent of patients hospitalized during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic were prescribed antibiotics on admission even though the antimicrobial drugs were rarely indicated at that point. The pandemic saw at least 29,400 deaths from hospital-associated antibiotic-resistant infections. Nearly 40% of those who died got the infection while hospitalized, according to CDC. The agency also reported that the antimicrobial-resistant hospital-onset infections and deaths jumped by at least 15% during the first year of the pandemic.

These findings represent major setbacks in the substantial progress made in combating antimicrobial resistance from 2012 to 2017. In response, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) released a statement summarizing lessons learned about antimicrobial stewardship during the pandemic and offered guidance on antibiotic use in hospitals during public health emergencies.

“We just need to remember evidence-based medicine and practice from those principles,” said Alan Gross, PharmD, a coauthor of the SHEA statement. “We should consider how much evidence we have for the interventions we're taking. If we don't have good evidence, we might be doing harm to the patient.”

Clinical uncertainty spurs antibiotic use

It may not come as a surprise that nonindicated antibiotic use rose in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The SHEA white paper identified several reasons for this. Among them were clinical uncertainty about signs of high-risk cases; providers’ discomfort with taking no action at all for patients; and a shortage of PPE, which limited provider interaction with patients and lowered the threshold for starting and leaving patients on antibiotics.

“At the end of the day, everybody's trying to do the best thing for the patient, so it's kind of the nature of the beast,” said Gross, who is a clinical associate professor in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Illinois-Chicago.

Add to that low threshold for starting antibiotics a high suspicion for co-occurring bacterial infections among patients hospitalized for COVID-19.

“There's often concomitant bacterial infections in patients with run-of-the-mill, community-acquired viruses, but with COVID, it was a shot in the dark,” Gross said. In retrospect, he added, it was likely fewer than 2% of patients admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 that had concurrent bacterial infections.

The paper outlines other common triggers of antibiotic use including uncertainty about the COVID-19 diagnosis at a time when tests could be unreliable and results could be delayed, and concerns about hospital-acquired bacterial infections.

Stick to evidence, even in a pandemic

The SHEA statement offers best practices for improving antibiotic prescribing in hospitals during breakouts of new infectious diseases.

The authors recommend that providers limit the initiation of antibiotics, particularly broad-spectrum ones, in admitted patients with high likelihood of a viral infection, such as SARS-CoV-2 or influenza. They stress that providers follow this guideline even in the absence of readily available and accurate diagnostic tests.

The statement goes on to detail the circumstances in which providers might consider use of antibiotics in a respiratory viral epidemic and which tests might be necessary after initiation of antibiotics.

Importantly, the authors address the critical role of antimicrobial stewardship programs during outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics, which should include monitoring emerging information and updates to national and international guidelines that are relevant to antibiotic prescribing; revising clinical recommendations relevant to antimicrobial use; and educating frontline health care providers on appropriate antibiotic use.

“We need to recognize the importance of antimicrobial stewardship programs and make sure that they are adequately resourced for future public health emergencies,” Gross said.